Courtesy of Health CMI-August 5, 2019

Acupuncture and herbs are effective for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Gansu Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (endocrinology department) researchers conducted a controlled clinical trial comparing drug therapy with acupuncture and herbs. Patients receiving both acupuncture and herbal medicine had a total effective rate of 96.67%. Patients receiving Chinese herbal medicine monotherapy had a 73.33% total effective rate. Drug therapy patients had a 53.33% total effective rate for the alleviation of DPN (diabetic peripheral neuropathy). [1]

Acupuncture and herbs are effective for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Gansu Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (endocrinology department) researchers conducted a controlled clinical trial comparing drug therapy with acupuncture and herbs. Patients receiving both acupuncture and herbal medicine had a total effective rate of 96.67%. Patients receiving Chinese herbal medicine monotherapy had a 73.33% total effective rate. Drug therapy patients had a 53.33% total effective rate for the alleviation of DPN (diabetic peripheral neuropathy). [1]

All patients were monitored throughout the investigation for adverse effects, including liver and renal function tests. No serious adverse effects were reported in any of the clinical trial groups, indicating a high degree of safety for all three treatment protocols. Outcome measures for the study included nerve conduction tests, TCM (traditional Chinese medicine) syndrome scores, and treatment efficacy rates.

Results

Nerve conduction tests were conducted on the common peroneal nerve (along the lateral aspect of the calf) and the median nerve (medial aspect of the forearm). For the common peroneal nerve, mean pre-treatment scores were 29.91 m/s in the drug monotherapy group, 29.91 m/s in the herbal medicine monotherapy group, and 29.90 m/s in the acupuncture plus herbs group. Following treatment, scores increased to 32.22 m/s, 36.62 m/s, and 39.92 m/s respectively.

For the median nerve, mean pre-treatment scores were 34.60 m/s in the drug monotherapy group, 34.60 m/s in the herbal medicine monotherapy group, and 34.56 m/s in the acupuncture plus herbs group. Following treatment, scores increased to 35.52 m/s, 36.52 m/s, and 39.60 m/s respectively. All groups demonstrated significant improvements. The acupuncture plus herbs group had the greatest improvements (p<0.05).

TCM syndrome scores were calculated by the participants subjectively rating symptoms including dry mouth and thirst, fatigue and lack of strength, shortness of breath and dislike of speaking, sweating, insomnia, limb numbness, and formication (the sensation of insects crawling on the skin). Each symptom was rated on a scale of 0–3, with higher scores indicative of severe symptoms. Mean pre-treatment TCM syndrome scores were 16.78 in the drug monotherapy group, 16.85 in the herbal medicine monotherapy group, and 17.54 in the acupuncture plus herbs group. Following treatment, scores fell to 13.47, 12.74, and 9.68 respectively. Improvements were the greatest in the acupuncture plus herbs group (p<0.05). Treatment efficacy rates were calculated for each group. Patients whose self-rated symptoms had fully resolved and whose reflexes were normal, with nerve conduction test improvements of ≥5 m/s, were classified as recovered. For patients whose self-rated symptoms and reflexes had clearly improved, with nerve conduction test improvements of 2–5 m/s, the treatment was classified as effective. For patients with no clear changes in their condition, the treatment was classified as ineffective. In the drug monotherapy group, there were 2 recovered, 14 effective, and 14 ineffective cases, giving a total effective rate of 53.33%. In the herbal medicine monotherapy group, there were 5 recovered, 17 effective, and 8 ineffective cases, giving a total effective rate of 73.33%. In the acupuncture plus herbs group, there were 11 recovered and 18 effective cases, with 1 ineffective case, yielding a total effective rate of 96.67%. Design A total of 90 DPN patients were recruited for the study and, using a random number table, were assigned to either the drug monotherapy group, the herbal medicine monotherapy group, or the acupuncture plus herbs group. The drug monotherapy group was treated with epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor used in the treatment of DPN. The herbal medicine monotherapy group was treated with Tao Hong Si Wu Tang. The acupuncture plus herbs group was treated with Tao Hong Si Wu Tang in combination with acupuncture. Baseline The drug monotherapy group was comprised of 16 male and 14 female patients, ages 40–74 years (mean age 57.60 years). The participants in this group were diagnosed with diabetes for 5.5–21 years (median duration 9.8 years) and suffered from DPN for 1.2–6.8 years (mean duration 4.3 years). The herbal medicine monotherapy group was comprised of 16 male and 14 female patients, ages 41–72 years (mean age 57.03 years). The participants in this group were diagnosed with diabetes for 5–18 years (median duration 9.6 years) and suffered from DPN for 1.5–7.0 years (mean duration 4.3 years). The acupuncture plus herbs group was comprised of 17 male and 13 female patients, ages 40–75 years (mean age 59.03 years). The participants in this group were diagnosed with diabetes for 5–20 years (mean duration 9.5 years) and suffered from DPN for 2–7 years (mean duration 4.5 years). There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between the three groups (p>0.05).

Diagnostics

Diagnostic criteria included a previous history of diabetes with signs of DPN present either at the time of (or after) diagnosis, signs and symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of DPN such as pain, numbness, formication (the sensation of insects crawling on the skin), and other abnormal sensations. The participants’ reflexes were tested including the ankle jerk reflex and responses to needle pain, vibration, pressure, and heat. In the absence of clinical symptoms, two of the above reflexes were required to be abnormal for inclusion in the study.

Further inclusion criteria included the age range of 40–70 years with a clinical diagnosis of DPN, fasting blood glucose levels of ≤8.0 mmol/L, postprandial blood glucose levels of ≤10.0 mmol/L, diastolic blood pressure of 60–90 mm Hg, and systolic blood pressure of 90–140 mm Hg. All patients were required to give informed consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included infections, external trauma, chronic alcoholism, malnutrition, drug-induced nerve dysfunction, concurrent cardiovascular, respiratory, digestive, neurological, hematologic, immune, endocrine, or psychological disorders, pregnancy, or simultaneously participating in other clinical trials.

Acupuncture, Herbs, And Drugs

All patients received appropriate dietary, exercise, and health education with the aim of regulating blood glucose levels. Any patients taking medications for blood pressure, cholesterol, or coronary heart disease maintained their original treatment and dosage throughout the study period.

Participants in the drug monotherapy group were treated with epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor drug commonly used in the treatment of DPN. A 50mg dose was prescribed, to be taken three times each day. Participants in the herbal medicine monotherapy group were prescribed Tao Hong Si Wu Tang comprised of the following herbs:

Dang Gui 15g

Bai Shao 15g

Chuan Xiong 10g

Shu Di Huang 15g

Tao Ren 15g

Hong Hua 15g

The herbs were decocted in water daily and were split into three doses to be taken morning, noon, and evening. Participants in the acupuncture plus herbs group were prescribed the above herbal formula and also received acupuncture treatment administered at the following acupoints:

Sihua points: Geshu (BL17), Danshu (BL19)

Feishu (BL13)

Pishu (BL20)

Shenshu (BL23)

Yanglingquan (GB34)

Sanyinjiao (SP6)

Quchi (LI11)

Bafeng (MLE8)

Baxie (MUE22)

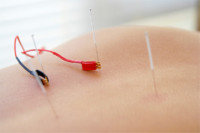

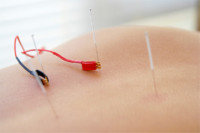

Needles were inserted using the standard method and, after the arrival of deqi, were manipulated for 30 seconds using a balanced reinforcing-reducing method comprised of twisting, rotating, lifting, and thrusting. Manipulation was repeated at 10-minute intervals and needles were retained for a total of 30 minutes. Treatment was administered daily.

All three treatment groups received two full courses of treatment, with each course comprising two weeks. During the treatment period, patients were advised to avoid cold temperatures and drafts, emotional stress, and overexertion, while refraining from smoking, drinking alcohol, and eating spicy, fatty, or greasy foods.

The results of this study indicate that acupuncture combined with herbal medicine is a safe and effective treatment for DPN and its associated symptoms. Acupuncture and herbs outperformed epalrestat and all treatment modalities used in the study had a low risk of adverse effects.

Reference:

1. Wu Guannan, Meng Caizhou, Zhang Dinghua (2019) “Randomized controlled study of acupuncture combined with Taohong Siwu Decoction in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy” Journal of Gansu University of Chinese Medicine Vol. 36 (1) pp. 64-67.

Acupuncture and herbs are effective for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Gansu Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (endocrinology department) researchers conducted a controlled clinical trial comparing drug therapy with acupuncture and herbs. Patients receiving both acupuncture and herbal medicine had a total effective rate of 96.67%. Patients receiving Chinese herbal medicine monotherapy had a 73.33% total effective rate. Drug therapy patients had a 53.33% total effective rate for the alleviation of DPN (diabetic peripheral neuropathy). [1]

Acupuncture and herbs are effective for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Gansu Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (endocrinology department) researchers conducted a controlled clinical trial comparing drug therapy with acupuncture and herbs. Patients receiving both acupuncture and herbal medicine had a total effective rate of 96.67%. Patients receiving Chinese herbal medicine monotherapy had a 73.33% total effective rate. Drug therapy patients had a 53.33% total effective rate for the alleviation of DPN (diabetic peripheral neuropathy). [1] Wonderful article by Kelsey Roy:

Wonderful article by Kelsey Roy:

SHARE

SHARE TWEET

TWEET EMAIL

EMAIL MORE

MORE